Dollar cost averaging

(I accidentally published an unfinished draft of this post a few days ago – sorry about that).

There’s a lot of sources preaching the benefits of dollar cost averaging, or the practice of investing a fixed amount of money regularly. The alleged benefit is that when the price goes up, well, then your stake is worth more, but if the price goes down, then you get more shares for the same amount of money. According to Wikipedia, it “minimises downside risk”, about.com says it “drastically reduces market risk”, and an article on Nasdaq.com claims that it’s a “smart investment strategy”.

This is nonsense if you think about it. You never benefit from a price going down. The stock market is mostly efficient and if it goes down by 1% then it’s as likely to go down further as it is to come back up.

Separately, it’s generally a false dichotomy to talk about dollar cost averaging as an investment strategy, since it makes it seem like there are other equally viable strategies available. For the average person who wants to save money by investing it in to the stock market, there’s really no choice between strategies. Given that the stock market is expected to go up, the earlier you invest, the better. So the best strategy is always to invest your money as soon as you can.

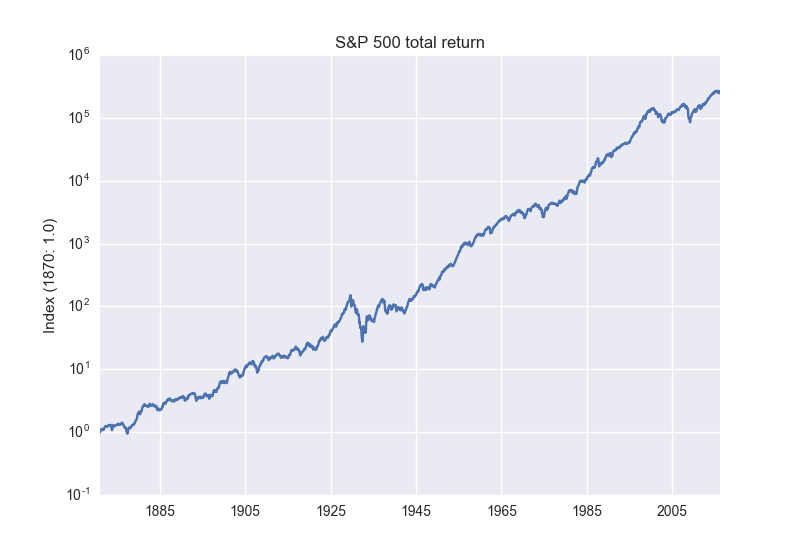

So if you invest say $100 every week, is that inherently a lot less risky than going all-in with a $1M investment and holding it? Are we more protected from market downturns? I downloaded S&P 500 data going back to 1870 and wanted to take a look.

The key thing here is to use the total return, i.e. with dividends reinvested, or you will understate the yield. You can get the data here.

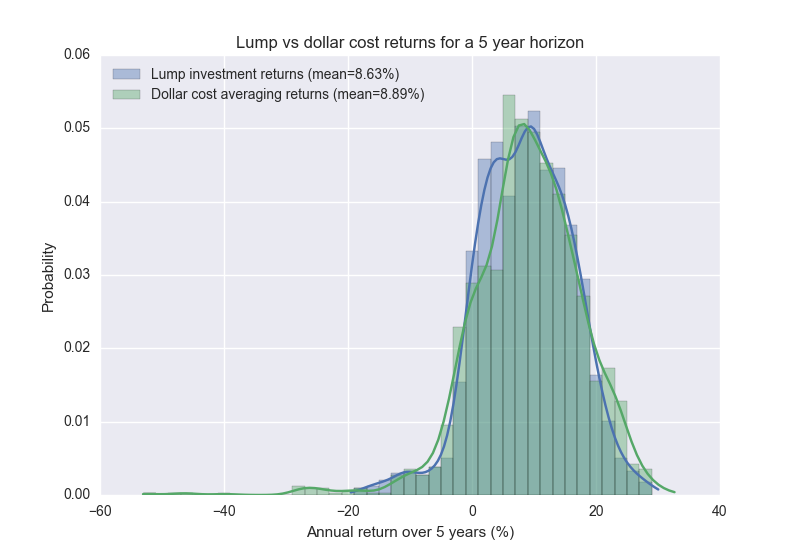

Comparing lump sum vs dollar cost averaging is a bit weird since the cash flows are so different. One way you can do it is to compute the internal rate of return. Let’s look at five year investment horizons and what the value of a dollar cost averaging strategy would give us, versus a lump sum investment

We see that there’s a improvement in using DCA although it’s quite small – an additional return of about 25 basis points every year. However the simulation shows that dollar cost averaging actually is more likely to be in the red five years later, 12.9% compared to 11.0% for a lump sum investment.

If you look at it a bit closer, it turns out none of these differences are statistically significant. The conclusion here is that the difference, if it exists, must be very small

How to compute IRR

Computing internal rate of return (also called annual percentage rate) is a fun little numerical problem. You want to find the rate $$ r $$ such that the cost of payment stream is equal to zero:

$$ \sum_i c_i (1 - r)^{-i} = 0 $$

where $$ c_i $$ is the payment/income at time $$ i $$. Or if you use continuously compounding rates you have the equivalent relation $$ \sum_i c_i e^{-i} = 0 $$. Either way, it’s the same problem as finding the roots of a polynomial. numpy.irr has a pretty terrible implementation of this that’s extremely slow. I ended up open sourcing a very simple implementation that uses binary search.

Notes

- Vanguard put together a presentation getting to the same conclusion. Another article from Betterment is also quite good.

- All code is available as a gist.